Spinster Science

The science and art of creating yarn and fabric through wool preparation has long been associated with women, even lending the professional title of “spinster” to old, unmarried women in Western society. As an industry, spinning has created independence and income for many women, while allowing them to adhere to strict boundaries and gendered expectations of a patriarchal society. The chemical and physical process of turning animal fleece into fabric requires skill and knowledge, and spinsters and their products have been crucially important to the development of many societies and cultures for thousands of years

Among the goods in a 26,000 year old grave found in the Czech Republic, archaeologists discovered the remains of a drop spindle alongside the remains of natural fibers meant to be used with the spindle. While there have been examples of both genders taking part in these crafts, spinning and fiber production was often conducted by women, starting as early as the Iron Age in Europe. In fact, some archaeologists have suggested that the presence of spindles within ancient burial pits can help identify the gender of the human remains even before skeletal analysis has been performed.

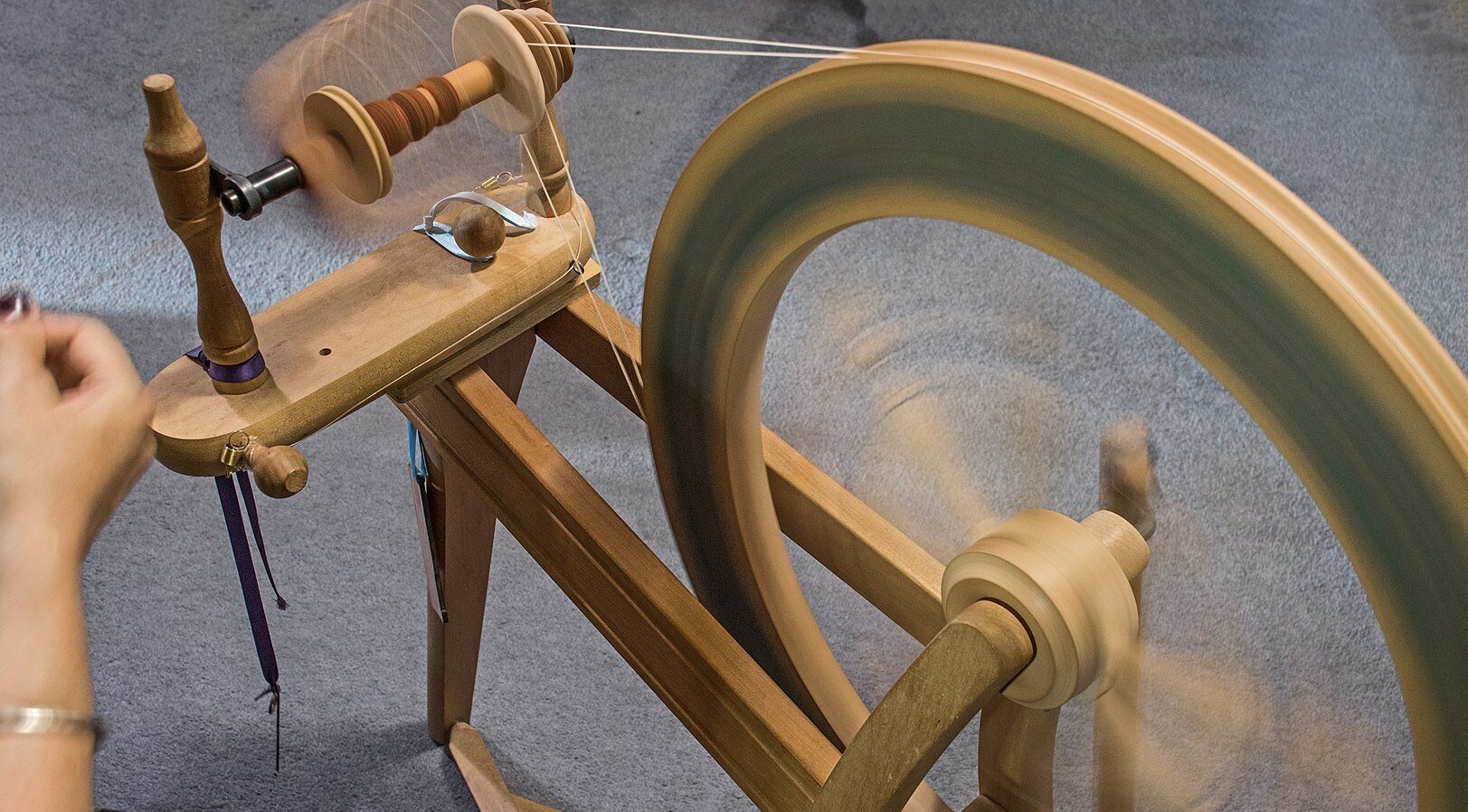

Spinning is the physical process of turning fiber—from plant, animal, or even mineral sources—into string material that can be processed into fabric. Those natural fibers have been cultivated since the beginning of farming. Spinning materials have been used since the Upper Paleolithic period and were continuously developed into different methods of creating yarn and thread for fabric making. In order to be spun, a strand of fiber must easily “catch” to another, forming a continuous string. This is why the fibers from many ungulates, such as sheep, can be spun into yarn, but human hair cannot. Using both tension and the weight of the yarn, the spinner pulls out a longer thread and winds the completed yarn onto a spool. The yarn or thread can then be processed through hanging and stretching, usually with a variety of different chemicals such as lye, soap, dye, and even human urine. The processed yarn is typically wound into a ball or other form of wrapped containment to allow knitter or weaver to keep it in order while making fabric. Ultimately, the fabric is made into clothing, bedding, and other household goods.

How spinning became women’s work is a complex phenomenon. Spinning was often done in quiet environments at home, allowing the worker to stop and start as needed, and as a result, the task often fell to women. Naturally, this craft required skilled practice and to be done in a fairly controlled environment, a kind of home textiles laboratory. Anthropologist Judith Brown in her 1970 paper, “Note on the Division of Labor by Sex,” argues that in early human cultures the art of spinning was best attuned to the members of a society who were constantly doing multiple tasks at once that require routine practice. For women, the creation of fabric was a task that could be combined with childcare. Spinning and weaving could be picked up and put down as needed, and it was relatively easy to do at the side of other activities such as attending children or nursing a baby. Textiles scholar Elizabeth Barber also argues for this, saying that if one is responsible for a wide variety of tasks, such as food preparation, child care, and housework, having tasks that are easily stopped and started again at the same place helped lead to production of a finished item that could be used for practical purpose.

“Even though women were being paid for this skilled and important labor, their male counterparts who worked with the yarns they made often received credit for women’s design and industry. “

Barber has shown that unmarried or widowed women often found themselves picking up extra money by spinning on the side. Even though women were being paid for this skilled and important labor, their male counterparts who worked with the yarns they made often received credit for women’s design and industry. In the 18th century, for example, complaints from male weaving guilds in England indicated that American textile workers, mostly women at home, were a threat to their dominance in the textile industry, and to Britain’s control over America.

Spinning became a factory-oriented process during the Industrial Revolution, and women spinners were ultimately replaced by machines. But the creation of threads and fabric was still dominated by a working class of women, many of them children and immigrants working in textile factories. Like spinning from the previous century, industrialized textile production allowed unmarried girls and women the ability to earn a small amount of pay. However, the conditions couldn’t be more different from those of home-spinners. Factory workers had to quickly learn patterns, identify fibers, and work with complicated, dangerous machinery, often for very low pay in poor conditions. When spinning and fabric-making moved from the hearth to the factory, the profits of women’s labor still accrued to the men who owned the companies and factories.

Traditional modes of yarn-making and hand-spinning, like many complex skills developed largely by women, have been relegated to the craft and hobby realm. After the advent of machines and the rise of leisure activities, spinning was no longer a sign of a women’s knowledge, rather it indicated that she had ample free time to focus on crafting. While many still view spinning, knitting, and sewing as a novelty craft, some women scientists are reevaluating the craft through the lens of science, showing that these skills are mathematically and technologically complex. Even though it shouldn’t take science to tell women what they’ve known about this skill for centuries, it’s refreshing to see people take women’s work seriously as something much more than a frivolous pastime.

Image credit: Spinning wool using Ashford Traditional spinning wheel (Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA 4.0)