Feminist Interventions in Nuclear Energy Debates

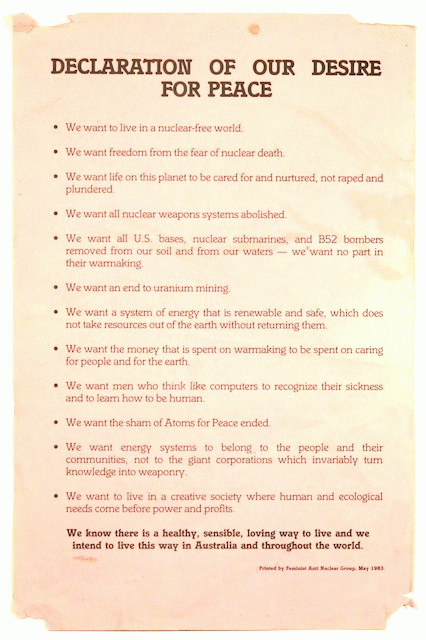

“We know there is a healthy, sensible, loving way to live and we intend to live this way in Australia and throughout the world” —so declared the Australian activist collective Feminist Anti-Nuclear Group (FANG) in May 1983.

FANG was one of many feminist collectives around the world engaging in the global debate on nuclear weapons and energy during the Cold War period. Theirs was a systemic critique that linked nuclear weapons and energy to broader eco-social and socio-economic relations. FANG is just one example of feminist activists, researchers, and future imaginaries during this period that were grounded in a growing understanding and elevation of the diverse labors, knowledges, experience, and values of women, which had been devalued and made invisible in dominant Western societies. The feminist anti-nuclear movement was characterized not only by critique of nuclear war and energy but by feminist energy advocacy that sought to dismantle centralized, corporate energy and usher in decentralized, community energy.

As has been documented extensively, women were at the forefront of the global anti-nuclear movement, particularly during its peak in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Despite often being dismissed as anti-tech greenies or hysterical mothers, women’s interactions with the anti-nuclear movement were generally complex and nuanced. In Australia, alongside FANG, other feminist anti-nuclear collectives included Women’s Action Against Global Violence (WAAGV), Women Against Nuclear Energy (WANE), and Wimmin for Survival.

Declaration of our desire for peace, FANG poster 1983. Photograph by the author, used with permission from the Jessie Street National Women’s Library

The women involved in these collectives articulated connections between ecological destruction, patriarchy, capitalism, colonialism, and energy systems—from peace movements focused on the threat of nuclear war to anti-uranium movements focused on the impact of uranium mining and nuclear energy on the health of people and planet. The crux of Australian feminist anti-nuclear collectives’ opposition to nuclear technologies largely stemmed from systemic critique based on previous experiences dealing with the psychological, social, ecological, and economic fall-out of patriarchal, capitalist domination and control over global politics.

When campaigning against nuclear war, these collectives drew upon a variety of war experiences: bearing the psychological burdens of caring for returning war veterans from previous wars, often long after the state had abandoned them; the traumatic experience of women’s bodies being weaponized through rape as a tactic of war; the grief of losing children, partners, family, and friends to previous wars; and being used as economic playthings—a cohort of surplus labor to be used in the war effort and then neatly returned to lives of drudgery and unpaid labor as housewives.

Women’s opposition to nuclear energy was grounded in previous chemical use and weapons testing that had impacted women’s health and the health of children, such as the fatal experience of the radium girls and early nuclear weapons testing in Australia and the Pacific Islands, and the ongoing exploitation and disenfranchisement at the hands of powerful corporations and male-dominated governments. They drew inspiration from growing connections between feminist, environmentalist and Indigenous movements that exposed environmental racism and sacrifice zones and from a deep desire to live more harmoniously with our living planet. Women are not innately more attuned to nature, but these collectives recognized that the lived experiences of women as caregivers and providers gave deep insight into humanity’s reliance on and connection with a healthy, living planet.

It was due to these, and the multitude of other concerns that were held about nuclear war and nuclear energy, that so many specifically feminist, anti-nuclear groups emerged worldwide during the Cold War. Similar collectives and campaigns outside Australia include the U.K.’s Greenham Common, the U.S.’s Seneca Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice and Women for Peace, and India’s campaign against the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant.

The grounding of feminist political projects in the diverse lived experiences of women was emerging as a key site of discussion and debate, not only in the anti-nuclear movement but also in many other spaces, including the scientific community. Feminist standpoint scholarship, a theory that knowledge is socially situated, i.e. that women have specific knowledges and understandings due to their social positioning, was gaining traction in the academy. Many scholars delving into this emerging research methodology were also participating in the feminist political movement and were shaping their scholarship in this political experience. Indeed, feminist sociologist Barbara Littlewood refers to feminist standpoint scholarship as the “academic response to the centrality that was being given to women’s experiences in the wider [feminist political] movement.”

In a 2019 article for Lady Science, media and cultural studies scholar Tina Sikka outlined characteristics and debates related to feminist science. These debates around feminist science continue today, including valid critiques of feminist standpoint theory, but were occurring in more emergent forms around the same time as the peak of the anti-nuclear movement. This is not to suggest that feminist science and the anti-nuclear movement were directly linked, or that these were the only two spaces that women’s lived experiences were being drawn upon for political or scientific projects. It is instead to highlight how during this period women’s diverse labors, knowledges, experiences, and values were guiding feminist research, feminist activism, and feminist future imaginaries.

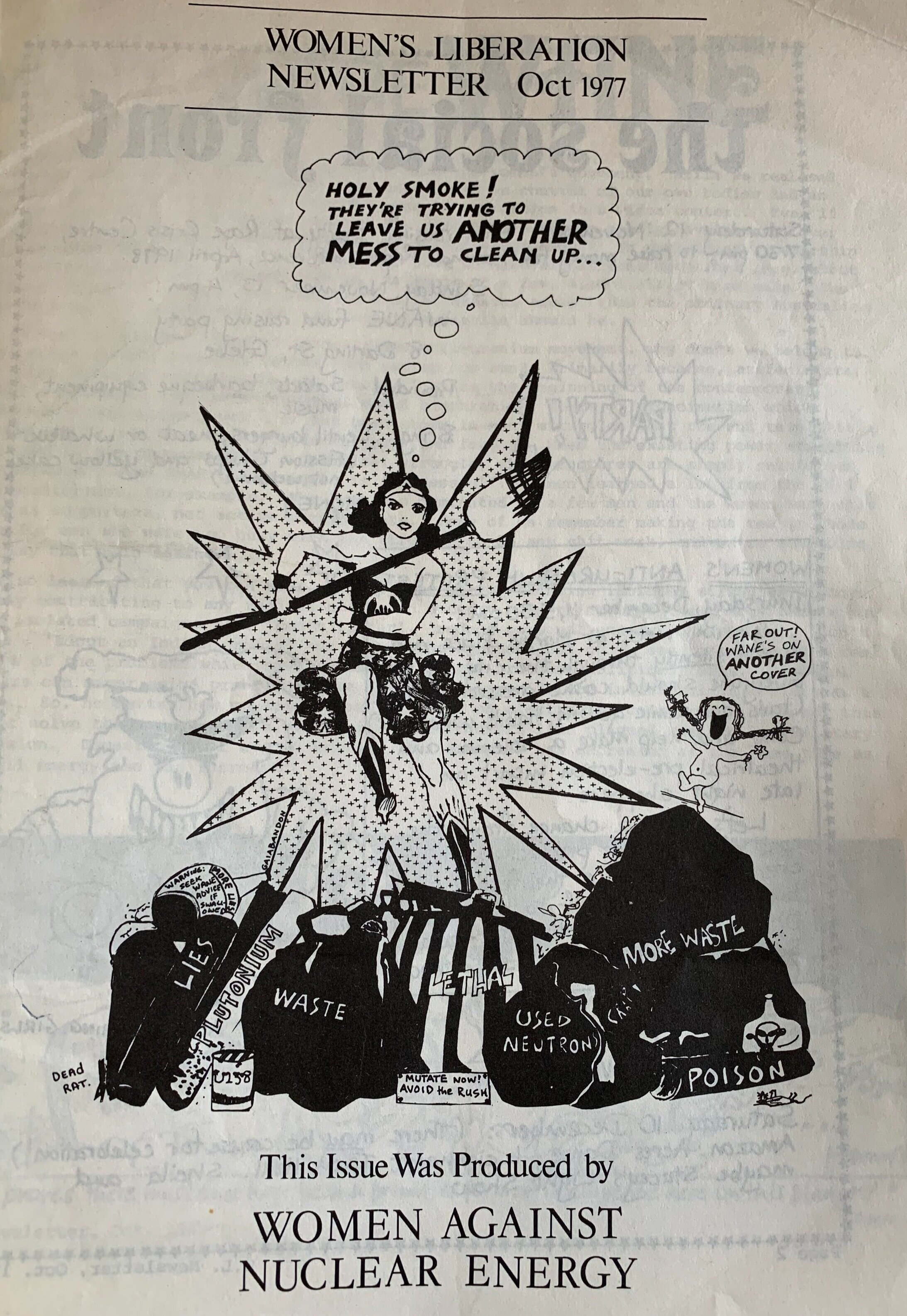

Sydney Women's Liberation Newsletter Cover Image of Wonder Woman wielding a broom over bags of waste, Oct 1977. Photograph by the author, used with permission from the Jessie Street National Women's Library

In October 1977, WANE explained in the Sydney Women’s Liberation Newsletter why they had formed a women’s anti-nuclear group. “While we realised the importance of specific women’s struggles (such as control of our own bodies and an end to job discrimination), we also saw women’s oppression in a wider context,” they stated. “Even if we won the right to abortion on demand, for instance, would we really have control over our own bodies when we can’t escape the poison in our environment?”

WANE also called into question technological determinism and the elevation of technocrats during the global nuclear weapons and energy debate. In the Women’s Liberation Newsletter, they wrote:

We also feel that the division between social, moral and ethical arguments on the one hand and technical rationales on the other must be challenged. The decision over uranium is not one for experts but for ordinary Australians. The prominence of (male) ‘experts’ on uranium...makes people believe that they cannot possibly make a decision on the question since scientific knowledge is beyond them. We think that the technological and economic aspects of the uranium issue can be expressed in ordinary language and are quite within most people’s grasp.

The collective demonstrated a desire of anti-nuclear feminists to democratize science and to ensure the false binary between social and technical decisions was no longer perpetuated.

Arguments such as these highlight how many women involved in the anti-nuclear movement were not “anti-technology” or “unscientific” as they were often disparaged. Instead, they understood the subjective, masculine nature of dominant scientific thought and sought to demystify and use critical, scientific thinking to build better futures for people and the planet.

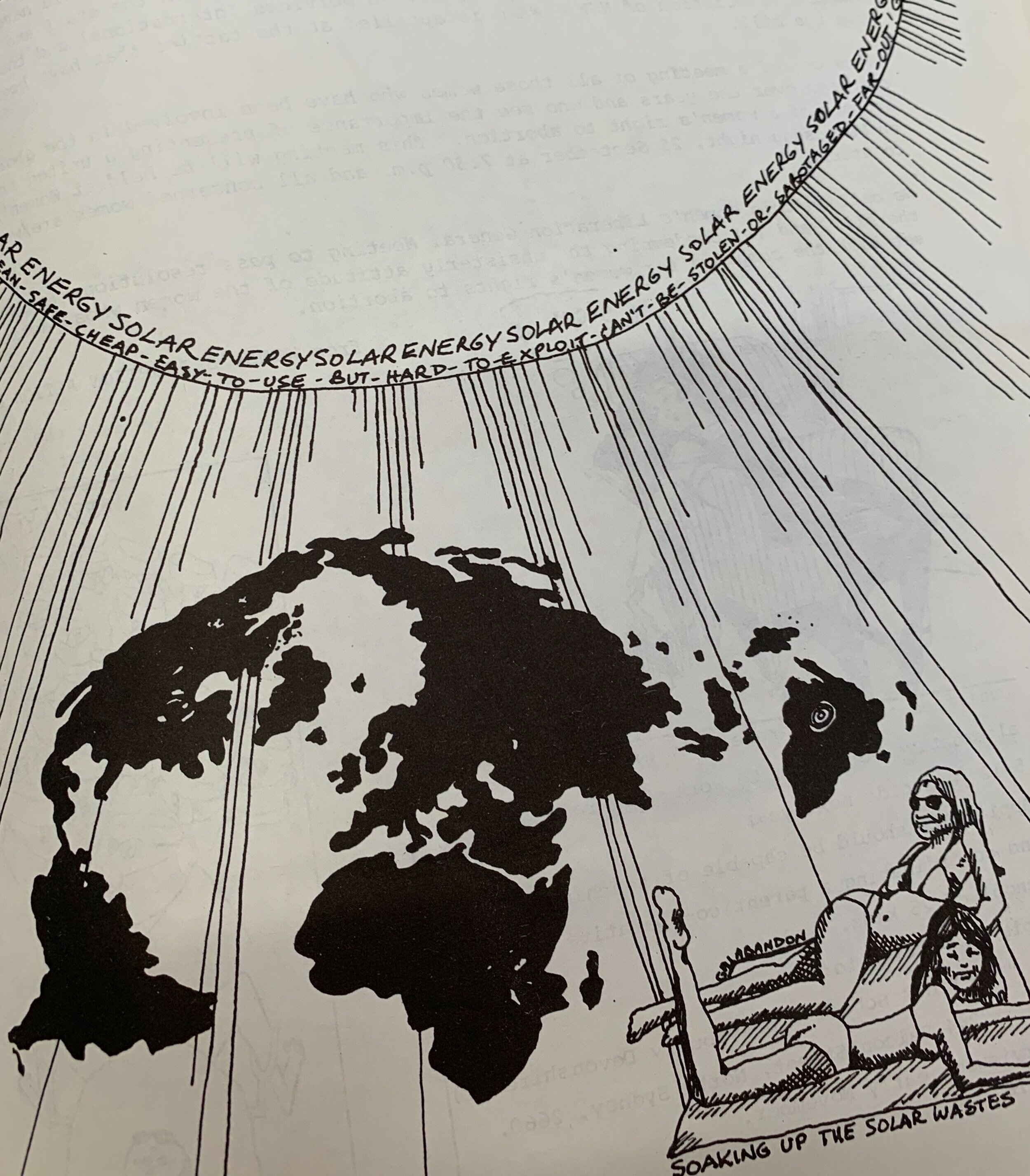

Part of this future-imagining and future-building centered on alternatives to nuclear energy, and as the threat of the climate crisis became more apparent, on alternatives to fossil fuels. Anti-nuclear feminist activism often included early feminist solar imaginaries in which the technology of renewable energy, particularly solar, was used to imagine futures that centered care, regeneration, and reciprocity.

The biophysical logic of renewable energy (i.e. sun and wind are everywhere) allows for the decentralization and democratization of energy systems. Anti-nuclear feminist groups recognized this potential and conjured up feminist energy imaginaries where energy was derived from the wind and sun, collectively owned and locally sourced. In these imaginaries, human-nature relations were more harmonious, and there was greater focus on joy, leisure, and spending time with one another.

FANG Newsletter, June 1983. Two women sunbathing to promote solar energy, with the caption “Soaking up the solar wastes.” Photograph by the author, used with permission from Jessie Street National Women's Library

Clearly, more than a transition in energy sources would be required for these imaginaries to come to fruition. However, the inclusion of energy systems in these imaginaries highlights the connections that feminist anti-nuclear activists were making between centralized, corporatized energy systems that were destructive to the planet, and decentralized, community owned and controlled energy systems that were more in harmony and collaboration with nature.

As we face another global debate on our energy futures, we can look to these nuanced, gender-literate critiques of energy systems and the liberatory energy imaginaries of anti-nuclear feminist activists and consider the paths we are advocating. Renewable energy has the potential to contribute to caring, regenerative, and reciprocal eco-social and socio-economic relations. But that does not mean that it necessarily will. Sikka highlighted why we need feminist climate science and suggested how we might get it. I suggest that to strengthen feminist climate science, we also need feminist energy advocacy. Through looking back to anti-nuclear feminism, we can build feminist interventions into energy activism and debates to reignite their liberatory dreams for renewable energy futures.

Further Reading

Eschle, Catherine. “Gender and the Subject of (Anti)Nuclear Politics: Revisiting Women’s Campaigning against the Bomb1.” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2013).

García-Gorena, Velma. Mothers and the Mexican Antinuclear Power Movement. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1999.

Liddington, Jill. The Road to Greenham Common: Feminism and Anti-Militarism in Britain since 1820. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. 1991.

Merchant, Carolyn. “Earthcare: Women and the Environment.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 23, no.5 (2010), 6-40.

Nelkin, Dorothy. “Nuclear Power as a Feminist Issue.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 23, no.1 (1981), 14-39,

Image credit: Nuclear power plant Dukovany, en:Czech Republic. Photo taken by Petr Adamek i October 2005 (Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain)