Bonus: Talking 'The Disordered Cosmos' with Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

Host: Leila McNeill

Guest: Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

Producer: Leila McNeill

Music: Breathe by Metre (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Rate. Review. Subscribe.

In this bonus episode, Leila talks with Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein about her new book “The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey Into Dark Matter, Spacetime, & Dreams Deferred”: why exploring what we don’t know about the universe is just as important as what we do know; what is the physics of melanin; what can physics teach us about the gender binary; why is the freedom to look at the night sky a basic human right?

Transcript

Transcription by Julia Pass

Leila: Welcome to this bonus episode of the Lady Science Podcast. I am one of your regular hosts, Leila McNeill, and I'm excited to welcome back to the show Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein. She is a theoretical physicist and an assistant professor of physics and core faculty member in Women and Gender Studies at the University of New Hampshire. Today she is here to talk about her new book, The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred. So thank you for coming back on the show.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Thank you for having me again.

Leila: And so just to start us off talking about your book, could you tell us a little bit about the book and where it gets its name?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. So the book is a holistic look at the doing of physics. So I wanted to give people a big picture. This is physics from my perspective as a scientist and practitioner of physics, but this is also physics as a community, as a journey, as a social phenomenon. So rather than acting like all we do is calculate and there's no other aspects to a life in physics or the doing of physics, I wanted to give the bigger picture. Not just physics, but also astronomy.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: The title has a funny story, which is "The Disordered Cosmos" was the name of the blog that I kept while I was in graduate school when I was getting my PhD. And the name is inspired by the first paper I ever published, which is described in the book. I was trying to solve the cosmic acceleration problem using some ideas motivated by quantum gravity, and it had non-local disordered spacetime connections in it. So I was like, "It's a disordered cosmology." So when it came to writing my first book, I was like, "Well, obviously this should be called The Disordered Cosmos." And I'm a big Carl Sagan fan, so I'm pretty sure that that's also how "disordered cosmos" happened.

Leila: Well, in the first part of your book especially, you walk readers through what cosmologists and astrophysicists do know about the cosmos, but you also give a lot of attention to what we don't know. For instance, dark matter is still a mystery, what it is and if it is even real. And so I wanted to ask why, to you, is exploring what we don't know so important to our understanding of this book and your work?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. I can't remember exactly the title, and I hope I'm getting his name right, but there's a book by, I think, Stuart Fierstein, who's a professor, I wanna say, of neuroscience at Columbia University. The gist of it is basically that science is what we don't know.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So I think that students of science, particularly high school students and undergraduates, can get the wrong impression about what science is like because they're studying from textbooks. And when things appear in a textbook, it's because we understand them already and they're what we know, and so you can walk away with the impression that science is what we know. And actually science is for the most part about being comfortable with being confused, maybe is the better way to put it.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: We spend a lot of time being unsure because doing research, whether it's in science or in English literature, is always the boundary of our interpretive understanding. What do we know? What do we think we know? We're constantly pushing that boundary forward. And that's actually our task as intellectuals, is to push our boundary of what we know forward. But that also means living at the boundary of what we don't know.

Leila: I found that to be a refreshing approach to a popular science book. I just feel that a lot of the ones that I've read—obviously I've not read all of them—that that was just a really refreshing way to be introduced to the work that you're doing.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. I think that it's important to put something different out there. I'm not gonna name names, but I can think of examples of books that are on highly speculative ideas, particularly in physics, and I think there's a lot of currency for this in the publishing industry, of putting out books about really speculative ideas and then talking about those ideas as if they are known and verified. I really don't know what we're gaining from this besides selling books.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I understand how it works to sell books. I understand it intrigues people and that sort of thing. But also we have all these conversations about how people don't trust scientists enough, and I don't see how this helps with the trust issue if we can't even be very clear about what's speculative and what's known. I think it's fine to do speculative work. I'm a theoretical physicist. That's what I do, is speculative work. But if that's what I'm gonna do, I have to be comfortable being honest about it.

Leila: Yeah. One of the things that structures this book is physics as an analytical framework for many things. Obviously the cosmos, but also melanin, the gender binary, and the basic human rights of Black children. Can you talk a little bit about how physics provides a way into understanding these things?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So I have to say let's start with the gender binary thing because I have to make sure that I give citational credit here, is that there is an I think Iraqi-British drag queen named Amrou. And Amrou was at some point asked, I think in a Channel 4 UK interview, about their understanding of the gender binary. And they essentially said that it's like how particles are both particles and waves at the same time and that that was another way of thinking about the gender spectrum and about being nonbinary from their point of view. And I saw that and thought it was quite brilliant, and then a bunch of people sent it to me after I saw it.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And it's interesting to me that everybody immediately thought of Chanda, partly because I'm someone who has publicly identified myself as an agender woman, as someone who has discomfort specifically with the gender binary, even if my relationship to the idea of a sex different, even though I think that they're both complicated and both live on a spectrum.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I actually had written a chapter for the book called "The Anti-Patriarchy Agender." Sorry, I'm laughing at my own pun. I'm still really proud of it. And I actually rewrote the introduction of the chapter because I was like, "This analogy that Amrou is making is actually a really key one." Because also some of the fiercest critics of our efforts to make it easier for students and colleagues in academia to ensure that the right pronouns are being used for them or pronouns that they are okay with being used for them in public are being used, scientists have really been some of the fiercest critics of these efforts, like people claiming that it's not biological and all of this other garbage.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And then I was like, "But wait, scientists are also perfectly fine with it could be a particle and a wave at the same time, but you guys are upset that someone might feel like they're different genders on different days?" Come on now. Patriarchy is just so lazy and boring, and it's really annoying that we have to waste time on it because it's so lazy and boring.

Leila: Yeah. I thought that was such a good point in the book, where you were like, "Look, we're theoretical physicists, and we're thinking about all of these great many possibilities, but we can't allow for these types of possibilities, and we can't even manage to use someone's pronouns correctly." Come on.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: That's exactly it. People are always like, "Oh, it's hard. Handling racism is hard." I'm like, "We built the Large Hadron Collider, and we've mapped out a 14-billion-year timeline of the evolution of spacetime and everything inside of it." Now granted we're still really confused about what 95, 96% of the matter/energy content is. We have no idea what dark matter is. We're not sure what's causing cosmic acceleration. [Unclear 08:58] dark energy for reasons that I actually find annoying. I don't actually think I talk about that in the book, but for reasons I find annoying.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: But even so, we have pretty good confidence about several things that happened in the first three minutes of a 14-billion-year timeline and we know all this stuff about galaxies and we know enough that we've been able to identify that there's something like the dark matter, or modifications to gravity are necessary. But y'all are gonna tell me that you can't figure out how to treat Black students with respect? That's hard for you? That's a choice. That is 100% a choice, and it's about your priorities.

Leila: Can you also talk a little bit about "The Physics of Melanin"?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So this chapter of the book, it's based on an essay that I wrote for Bitch magazine. It was in the winter 2017 print issue. I say it's based on it because I really feel like they are almost two different creatures at this point. It was maybe the hardest chapter in the book to write, partly because there were difficult decisions that had to be made about how to open it and where I wanted the reader's attention to go.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: My original motivation for writing about this is that often when we talk about Black people and science, we're talking about histories of repression, whether it's because we were being treated as experimental subjects or it's because we were being marginalized from science. And in some sense "The Physics of Melanin" was inspired by the idea of what if I just thought about our bodies as part of the physical universe through the lens of the knowledge system that I am trained in?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So specifically through the lens of physics and not through the lens of biology, which I have never taken. I didn't take a full biology class in high school. I took it in summer school so I could skip it. I'm really very much a physicist through and through, and so I wanted to think about it like a physicist. So that was really what I was thinking about when I published the essay in Bitch.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And then when I was updating the chapter for the book, I was at a different place in my life. I was further along in my work in science, technology, and society studies. I was engaging a lot more with the scholarship of people in STS, as it is known, who think about race as a social construct versus these debates about whether it's biological and all of that stuff, and I felt a responsibility to attend to that. I felt a responsibility to attend more carefully to how we even got to a place where melanin is first the subject of this massive social debate and a very distant second or 100th subject of these physical questions. And so I think that really shaped the writing.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: But I would say even as the book was going through copyediting and then the first pass, in November was the first time that I hadn't made a major change to that chapter. So I'll just say it was the hardest one, and I expect it to be the one that is gonna be most difficult for people to be satisfied with maybe.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Maybe I shouldn't be telling people what to be unhappy about. That's my expression of I see all of the things that could have been done differently. And actually, I visited Ruha Benjamin's class at Princeton yesterday, and they read the essay, the Bitch version. And I said to them that I almost feel like this is something that should have had a book devoted to it instead of a chapter.

Leila: Is "the physics of melanin," is that your coinage?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yes.

Leila: Awesome. I thought that might be the case. And I also wanted to touch a little bit on how you see physics as a basic human right of Black children. And you do mention in the book that this is as much of a right as clean water and food.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I definitely think that in some sense that's maybe gonna be the most surprising thing for a certain set of readers, particularly since I think people are so used to, again, talking about science in these terms of we're either victims of it or being oppressed in it, etc. And I actually think maybe a really good example is Perseverance just landed on Mars. This was just in the last week. There was immediately a big social media discussion about "Well, why didn't we spend that money feeding people or housing people or something like that?"

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And I understand the impulse to have that thought, and I also understand this to be a product of people not really realizing exactly how big the distance is between billions of dollars and trillions of dollars or even millions of dollars and billions of dollars. It's like, "Oh, it's one more zero," but actually the percentages matter. And if we have people who aren't comfortable with big numbers, that can really get lost in the mix.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So I wanted to push people a little bit to rethink the conversation, which is rather than saying that we have to choose between being interested in the universe or saving Black lives, what about the idea that Black people are interested in the universe and that part of saving Black lives is giving Black people the conditions in which they can be curious about the universe? And that's partly my dream for myself. I want those conditions, and so in some sense I'm saying I wanna time travel and give my childhood self those conditions.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I can't actually do that, but at the very least I can write for the next generation. And that's in part why "dreams deferred," the Langston Hughes reference, is in the subtitle, is that I'm writing about dreams that I have had for myself that I know will be deferred to a generation that comes after me. And that's one of them, which is give us the conditions. And so just to draw the connection with clean water, etc., which is the conditions that give people the freedom to look at the night sky, to feel liberated to just sit down and wonder, is that you have to not have a care. You have to not be worrying about where your next meal is gonna come from. You have to not be worrying about like, "Is it safe for me to be outside at night?" or "What happens if the cops come across me standing outside looking around?"

Leila: Mm-hmm. Yeah. I do like when you connect that to history and you say that you want Black children to be able to look at the night sky in a different way than their ancestors did in that they're not using the night sky to navigate to freedom, but that they have the freedom to do that because the conditions have allowed them to do that. I loved that connection that you make to history and your ancestors.

Leila: And placing yourself in history is something that you do throughout the book. You place yourself in the history of physics, in the history of your ancestors. And in my experience it's really rare to see this kind of historical self-reflection in a science book. So how does this kind of reflection shape your work and the way that you see yourself in it?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. Oh, good question. I mean, I think that one way that I want to communicate to people about science is my personal perspective on what I'm doing as a scientist. And part of what I'm doing as a scientist, as I mentioned, we have this whole cosmological timeline. When I say a cosmological timeline, I'm talking about a story, and stories can be true, so I don't want anybody to say, "Oh, well, you're making it sound like it's fiction or something." I think it's a true story with maybe some mistakes in it because we're sometimes finding out that actually we didn't understand things as well as we did. But let's say that it's a fairly accurate story, but nonetheless it is storytelling. And I think that that framing of it is the one that makes sense to me as a scientist and it makes sense to me as a Black scientist. I'm not sure I can separate those two things.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And it is also the case that I know as a Black person that storytelling is part of my culture, as it is part of every community on Earth. I don't think I've ever heard of a human community that didn't have storytelling as a fundamental feature of culture. And so I think part of what I'm trying to articulate is a sense of continuity for people where often continuity for the idea of Black scientists is not articulated. The idea is that we are new, that there is somehow some kind of a historical break in which we arise, if you think Fred Moten's break, and that we exist in the wake of slavery and that we only exist in the wake of slavery as Christina Sharpe might articulate it.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And I think what I wanna say is that it's certainly the case that all of us who are alive today, whatever your socially assigned gender at birth, whatever racial category that you might fall into, that we all live in the wake of slavery. But there was a time before that, and we were doing the kind of intellectual work that we might label as science now before slavery. And I wanted to mark that in very clear terms partly because I think part of the struggle of being a Black scientist is articulating a sense of self, a sense of whole self where you don't feel like parts of you are at odds with other parts of you. And I think that that's partly socially imposed. When you're told that Black people don't do science, you're like, "Oh, I'm weird." You're not weird. You're part of a legacy.

Leila: There are personal aspects to this book, like when talking about your self-reflection and history and that type of thing, but the book certainly is not a memoir, and it doesn't read like a memoir. But you've posted on Twitter about the problem with publishers wanting you turn it into one, and with librarians categorizing it as a biography. And I wanted to get your thoughts on what's going on here with people tryin' to categorize your book in this way.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. I should say they're two different situations. So what publishers were looking at was a book proposal. So I didn't go to them with a completed manuscript. I went to them with a proposal that had an anecdote, that had a table of contents, that had some chapter summaries, and had a sample chapter. And I think the sample chapter was "The Physics of Melanin," which is an extremely not memoirish chapter.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And what happened with publishers is they would be like, "Oh, so we really like you as a writer." And I know they have to say that, but I also believe that they actually genuinely, and that's why they were speaking to me as if they thought I was a good enough writer. "But we really think that it would be great for you to do a memoir or to make it straight science." Which, for those of us like you and me, who work in science, technology, society studies/history of science/sociology of science, chafes a lot.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: They were basically like, "I know you believe that science and society co-construct, but could you just take out the society part and just say science constructs?" I almost feel like there's definitely a piece to be written there about how publishers of popular science actually drive this social view that people end up having about what science is by insisting that they will refuse to market anything that says something different. And my understanding of those conversations is very much that they were saying, "Well, we just don't know how to market what you're saying you would like to do."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And one of the reasons that I ended up with the publisher that I did is that Katy O'Donnell, my editor, she had been watching my writing and was like, "I want you to write that. I want you to write what is in you to be written." And I guess the one comment I'll make specifically about the memoir is that there were moments that it truly felt—

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Well, actually, I should say one person said, "What about an anti-Trump polemic?" and I was like, "Mm." Which, of course, also the timeline woulda been terrible because it would have been coming out in the first few months of the Biden administration. So that was a cynical, "Oh, he's probably gonna win a second term." I was like, "I'm not gonna gamble on that because my hope is that he doesn't."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: But just to come back to the memoir thing, I think also after Hidden Figures came out there was a market for consumption of the stories of Black women scientists, not for the sake of filling in gaps in our social timeline but for the sake of people love a story of travesty and trial and triumph and like, "You're a Black woman who's overcome things." And I actually don't want to be used like that. So that was part of it.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: With the Library of Congress and the subject classification, I wanna say, actually, the Library of Congress worked with me to address it, and I'm quite happy with the classification that appears on the copyright page of the book. Yeah. Yeah. My publisher was like, "How did you pull that off?" I was like, "I don't know." My agent was like, "She's so good with Twitter." I was like, "I don't know if that's how other people feel about it, but okay, I'll take it."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I think they were trying to figure out how to make sure that Black readers would get the book. This speaks to all kinds of problems with how libraries are thinking about how to get books into readers' hands and which books do readers need. But the idea basically was that if it was classified as African-American biography, that it would be put in the section where Black people go. I think that that was part of the thought. Which is not a terrible thought, that Black people might go to the African-American biography section, but then you have to ask yourself, "Well, why do you feel Black people aren't going to the science section? Why did you choose African-American biography but particle physics doesn't appear there? What role do libraries have in getting Black kids, Black teenagers, which is probably the appropriate level and up for the book, how do you get Black teenagers into the particle physics section? I wanna hear your plan for that."

Leila: Mm-hmm. Yeah. And I don't know if, probably not, white men science writers have the same issue with this.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: No. They do not. I checked. I checked this. And actually, the example that I immediately pulled from my shelf was Brian Keating's Losing the Nobel because that book actually arguably in some ways is a memoir because it's not primarily intended to be a popular science book even though that's part of what it does. But it's primarily the story of how Brian ended up not being a central figure in the [unclear 25:29] ultimately false announcement of detection of primordial gravitational waves back in 2014. And it's also a commentary on how the way that Nobel Prizes are awarded drives people to make these kinds of announcements before they've really ticked all of their boxes and done all of their scientific checks.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I pulled that book off the shelf, and it had one category. Well, maybe it had two. I'm pretty sure it had cosmology, and one it definitely had was science methodologies. And I was like, "But he talks about his father dying and his uncle and how he was treated on the experiment." And I reviewed the book. I said it was an important book, so this isn't me knocking it, but the contrast was extraordinary.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Subsequently, I think a few days after all this happened, I got a book in the mail, which I can't remember the title or the author—my apologies to everyone—by a white woman scientist who works on Mars. And on the book flap it talks about her personal journey starting as a child and developing an interest in Mars. And the only subject category that it was assigned was about Mars. So at some point you have to be like, "So what's the difference here?" It's not even particularly gender. It's not necessarily that white women are having a different experience. There was something very clearly like, "It said Black? Oh. Okay. Well, then, it has to have the Black-ass categories."

Leila: To wrap up the interview, you end the book with a love letter to your mother, Margaret Prescod. And can you talk a little bit about her and what part she played in the making of this book?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. So my mom didn't see any of my book until we were at the point where I needed to ask her if there was anything that she wanted taken out because we couldn't take anything out after that stage. But I think after the copyedits were sent to me and I had to respond to them, at that point I did my responses. And then I sent it to her, and I was like, "You have a week before I have to return this to my publisher, at which point they will start indexing and paginating. And that means that I can only change a couple words at a time and I have to count characters."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So I told her, "I need you to read the section on wages for housework and I need you to read this letter to you and I need you to tell me if you're okay with them." I also actually sent it to my dad and specifically told him, "Please read the wages for housework section" because I was talking about his mother, Selma James, in it. And to my surprise, honestly, my mom made a very mild edit to the letter. She asked me to take something out which I think I had been thinking about taking out anyway. And then she had way more to say about exactly how I had phrased the stuff about wages for housework. And I was like, "Look, it's not a history of wages for housework."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So lemme just say my mom has a hard time being the center of attention. Which can be surprising for people who have interacted with her in the sense that she's very outspoken, she's a forceful speaker, she's an incredible orator, she's an incredible lobbyist. If she wants something, she's gonna be on you about it, and she's good at it. And people often interpret this as her being very self- and ego-motivated, but she's truly motivated by the community.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: She continues regardless of what her socioeconomic circumstances have been at any point, and they've changed through time. Her commitment has always remained firmly with poor welfare mothers, for example, even though I was a WIC baby, but I don't think we were ever on welfare. So it's not exactly like, "This is my story, and I have to do the thing." She just has a real firm sense of right and wrong. And part of what I'm articulating in the letter is that I think I inherited that from her, which annoys people sometimes 'cause people are like, "Can't you just be more ego-driven and wanna sell more books?" Some of those conversations were hinging on "You could make more money if you did this."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I guess the last comment I'll make about that is that I wanted to surprise my mom, and I think she was surprised, but I don't think that there's ever really a way you can thank someone who has done all of the things that my mom has done for me and that I felt like one of the better gifts that I was ever gonna be able to give her besides making something of what she has given me was to actually basically have this giant public "thank you" that was gonna be in people's homes maybe forever and in libraries and to make sure that people knew her name and knew of her presence and impact. I also knew at the time that she was negotiating with HBO. There's gonna be a show about her.

Leila: Oh, my gosh. That's amazing.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: So I knew that what I said—and historians are finally starting to interview her because they're finally realizing that she's actually someone that feminist historians and historians of women's rights movements need to be talking to. But I wanted to make sure that my perspective on that also got put out there because I don't think anyone else can see it the way that I saw it growing up with her as the only child of a single parent.

Leila: That was a great way to end the book. Is there anything else that you want people to know about your work or about the book before we close up here?

C. Prescod-Weinstein: Yeah. I guess really over the last few days I've been getting some questions the extent to which I deal with alternative ways of knowing or indigenous ways of interpreting science. And I fear that people might be a little bit disappointed on this front because that's not really my ministry. I'm happy with my language for doing this cosmological storytelling, and I think it's okay that it's not my ministry.

C. Prescod-Weinstein: I understand that people are hungry for that, and I also hope at the same time that people accept that one person shouldn't have to be everything and do everything. My hope is that there will be a Black scientist, or maybe there already is one, for whom that is their thing, figuring out how interpretations of quantum mechanics speak to philosophies from maybe a West African community that they know because that's where their people are from or that's where they grew up, etc., and I hope that my book creates room for them to say, "Yes, it's okay for that to be my thing."

C. Prescod-Weinstein: And I hope also that my book creates room for them that when they say, "I'm ready to share this story with the public," that publishers are like, "We are ready to give you the spacetime to share that story with an audience without trying to mangle it into a polemic or a memoir or tell them, 'Don't mention Africa. Just mention, air quote, "straight science."'"

Leila: Mm-hmm. Publishers, quote-unquote, "taking a risk" and publishing things that aren't mainstream the way that your publisher took that chance with you, and now we have this book which is, I think, quite different than most popular science books out there and opening the door to other types of writing about science for sure. And I want to say a big thank you to you for being on the show and letting everybody know that The Disordered Cosmos from Bold Type Books will be released on March 9th.

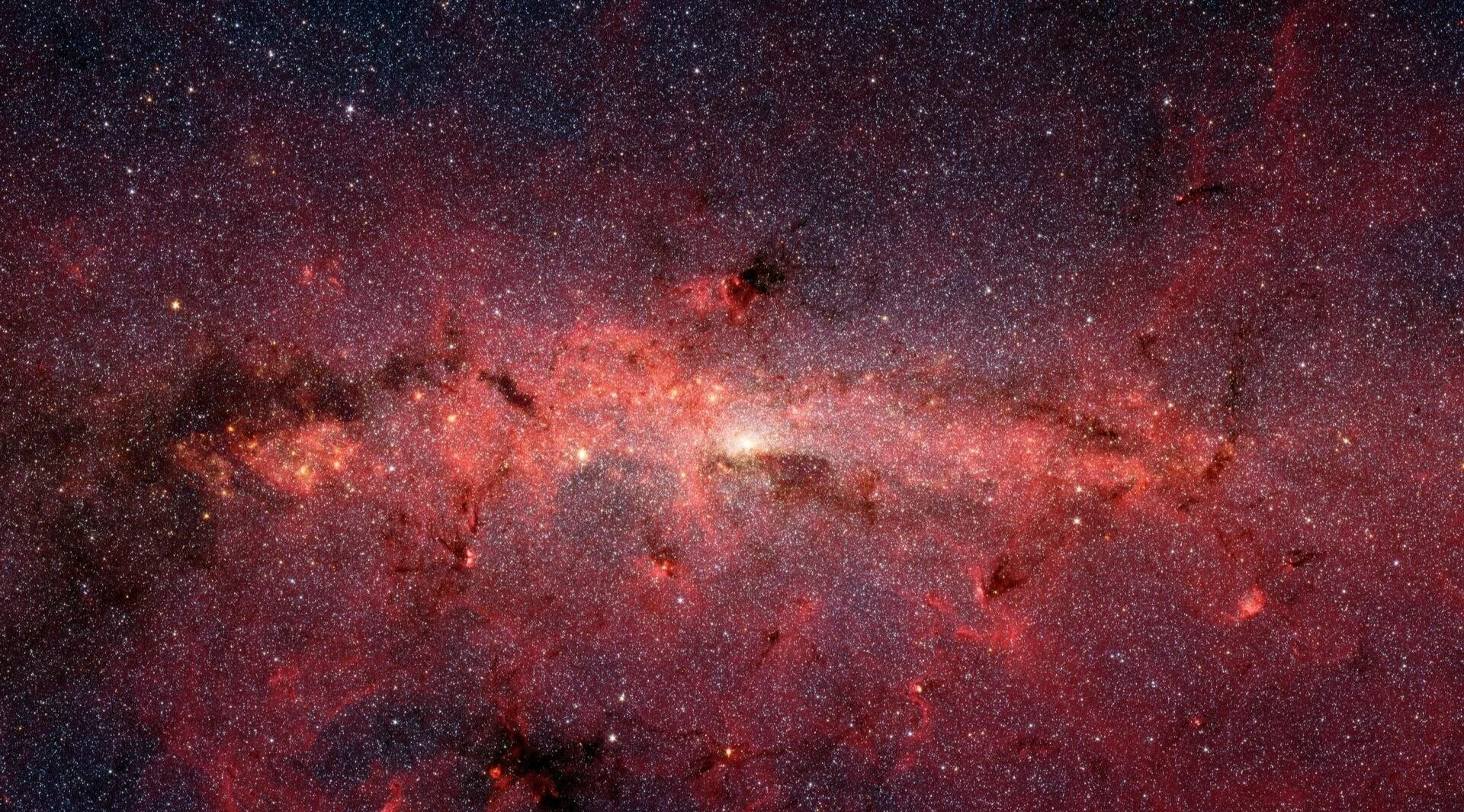

Image credit: A Cauldron of Stars at the Galaxy Center from the Spitzer Space Telescope shows hundreds of thousands of stars crowded into the swirling core of our spiral Milky Way galaxy, 2006 (NASA/JPL-Caltech)