Episode 1: PILOT!

00:50:04

Hosts: Anna Reser, Leila McNeill, and Rebecca Ortenberg

Guest: Jenna Tonn

Producer: Leila McNeill

Music: Careful! by Zombie Dandies

In our pilot episode, learn about Lady Science Magazine, meet its editors, and join our discussion about the history of nursing. We discuss the mythic representation of Florence Nightingale, and historian of science Jenna Tonn joins us to talk about the historical roots of the "naughty nurse" trope.

Show Notes

Florence Nightingale: Of Myths and Maths by Joy L. Rankin

Why Are We Still Talking About the Naughty Nurse by Jenna Tonn

Further Reading

Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History by Catherine Ceniza Choy

Black women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890-1950 by Darlene Clark Hine

American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work by Patricia D’Antonio

Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing by Susan Reverby

Transcript

Rebecca: Welcome to the first episode of the Lady Science podcast. Lady Science is an independent magazine about women in the history and popular culture of science, technology, and medicine. Whether dismissed outright, labeled witches or housewives, or forced to do their work on the margins of the scientific establishment, women have always been a constant presence and a formidable force in science. The story of science is often about the dogged and dangerous work of famous pioneers like Marie Curie, of course, but it is also about the ridiculed and marginalized practices of midwifery and domestic engineering and the unremembered women who were never given a chance to make their names.

Rebecca: This podcast is a monthly deep dive on topics that we address in the magazine, as well as about current events related to women in science and pop culture. You'll hear from writers who contribute to the magazine as well as historians, humanists, and other experts who work to recover the history of women in science. With you every month are the editors-in-chief and managing editor of Lady Science.

Anna: I'm Anna Reser, co-founder, co-editor-in-chief of Lady Science. I'm an artist, writer, and PhD student, and I study 20th century American culture and the history of the American space program in the 1960s.

Leila: I'm Leila McNeill, the other founder and editor-in-chief of Lady Science. Administrative science and freelance writer with words and various places on the internet. I'm currently a regular writer for women in the history of science at smithsonian.com.

Rebecca: And I'm Rebecca Wartenburg, Lady Science's managing editor. When I'm not working with the Lady Science team, I can be found writing about museums and public history around the internet, mostly on Twitter, and managing research projects at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia.

Leila: This launch of the podcast marks Lady Science's three year anniversary. Anna and I began Lady Science three years ago as a monthly newsletter, which we released on Ada Lovelace Day 2014. Living in separate places, Anna and I wanted to continue working together after graduate school, and starting a project about women in the history of science, technology, and medicine was a topic that we both cared deeply about. The newsletter consisted of two essays that were written by us for most of the first year. After the first year, the project grew as we launched our own website, grew our readership, and added in contributing editors and writers and expanded our content.

Anna: Now the magazine consists of two core essays published every month on topics related to women and gender in the history of science. We think of the definition of science very, very broadly, which means that we write about women who did things that are not often considered proper science. We've written about women spiritualists, midwives and Ufologists, as well as more traditional fields, like geology or physics. We focus on the social and cultural context of women's scientific activities rather than individual biographies in order to understand how and why women have been excluded from participating in science. Between monthly issues, we publish hot takes on current events related to our interests, special series like our recent technological memoirs, and a weekly digestive feminist reading from around the web.

Rebecca: Right now we have five fantastic contributing editors. Joy Rankin, Kathleen Shepherd, Jenna Tonn, Robert Davis, and Sam Muka, and about a dozen writers who have contributed work over the last three years. You can learn more about all of us on our website, ladyscience.com.

Rebecca: For this first episode, we'd like to talk about one of our favorite magazine issues from this past year. Back in February, we ran two essays about nursing. One of those essays was about the naughty nurse trope in history and pop culture. Jenna Tonn, the essay's author, will be joining us a little bit later to talk more about that. The other essay was written by our long time contributing editor, Joy Rankin, and it was about Florence Nightingale. In that essay, Joy explored a side of the famous nurse that we don't necessarily see. Now, usually we don't like to publish pieces about famous figures like Nightingale, not because we don't love them, but because they take up so much space in people's minds when they're thinking about women's history and women in science, but Joy's essay really does something different. Here, Florence Nightingale isn't a saintly, feminine lady with the lamp that most people have heard about. She's a mathematician who led an incredibly unconventional life for a woman of her time. Appropriately, Joy titles her essay Florence Nightingale: Of Myths and Maths.

Anna: Before Nightingale was a nurse, she studied mathematics as early as age 11. Nightingale's father made sure that she was educated, something that wasn't common for girls in this period. Nightingale was a keen student, and even asked for private math lessons, but her decision to enter the field of nursing was ultimately disappointing to her family. In 1854, Nightingale was sent along with a group of nurses that she had trained to care for wounded soldiers in the Crimean War. It was here, supposedly because she cut an ethereal figure making her rounds in the evenings, though she earned the moniker The Lady with the Lamp.

Anna: But Nightingale was also gathering data about her patients and the conditions of the hospital she worked in. She found that soldiers were more likely to die at home or abroad during peace time than they were during war because of unsanitary conditions in cities. She wrote an 850 page book called Notes on Matters Affecting Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army, a text that became a crucial part of hospital reform. Nightingale pushed her mathematical skill even further and developed the polar area graph to visualize causes of death from the Crimean War.

Anna: As a statistician, Joy argues that Nightingale saved more lives with mathematics than she did giving direct care as a nurse. Joy begins her article by saying, "The way we tell stories about women matters. The way we remember women matters." So, to sort of kick off the discussion, why, in the case of Nightingale, at least, does this matter? Why does it matter how we tell these stories about women?

Leila: I think this issue really boils down to representation, and this reminds me of the conversation surrounding trademark strong female characters in popular culture and how these women and their characters are usually written as flat characters with little to no motivation and no complex inner life, and, similarly, with Nightingale representing her only as The Lady with the Lamp flattens her and diminishes the other work that she did, and it's been easier to see her as a nurse in a historically gendered feminized field rather than in mathematics, a historically masculine gendered field. And, I think mythologizing her as an ethereal woman who cared for men in the night also sugarcoats the truly gruesome work that nursing could be, especially battlefield nursing. I mean, this was war, after all.

Anna: Yeah, there's something almost infantilizing, I think, about this Lady with the Lamp idea in that her real value to these soldiers was not her direct work as a nurse, or even her statistical innovations, but that she was just sort of a comforting figure and a symbol of femininity in a sort of hyper-masculinized environment, and it's such a powerful image and it's sort of very sticky kind of romanticization of war in general that it's really difficult to get past that, which is, I think, what's so important about Joy's essay. And, like you said, talking about mathematics as a gendered field, a masculine field, and sort of putting Nightingale into that context really sort of upends, I think, the mental image that we associate with Florence Nightingale, and with nurses in general.

Rebecca: Yeah, I think that infantilizing really is the word for it. It also, in some way, sort of, I feel like medicine has weirdly looped back to being, today, a feminine field. I mean, for so long, women were not doctors in the traditional sense, but now, as more women become doctors, now we're back to, oh, well, medicine, at least general practitioner medicine, is sort of starting to be considered feminine again and given kind of these Lady with the Lamp category, giving Lady with the Lamp category to it. I don't know, it does seem relevant to, sort of, women in medical care even more broadly in this way that we kind of are able to put women in medical care in this particular box by giving it these feminized qualities.

Leila: Yeah, and one of the things that we don't typically do in the magazine, like Rebecca mentioned, was that we cover in detail some of these big names of women in history that we all kind of know about, and Florence Nightingale is one of those. And the reason we don't really talk about those big names is because that they do overshadow the work done by everyday women. So, in this case, we remember Florence Nightingale, but we don't remember the hundreds of nurses that she trained and the ones that were also in Crimea. But I think it's still important to examine her life and legacy, because, as Joy shows, we haven't really done a great job of telling her life and legacy to begin with. And I don't think we need to stop talking about these big names, but we do need to be more mindful of how we tell these stories and to what ends we're using them. I don't know, what do you guys think?

Rebecca: Yeah, definitely, and I think that, especially because the way in which we talk about big names can have a pretty significant effect on how we talk about everyday women. So, Joy, in the essay, points out that nursing as a profession has been defined by the Nightingale myth. And like I was saying before, I think there's a certain degree to which women in medicine generally have been defined by that myth. So, because she's delicate and feminine, nurses are delicate and feminine, or she's kind and self sacrificing, and so nurses are kind and self sacrificing, and you're only able to give them the qualities that maybe Florence Nightingale was given. And so, if she's a rigorous scientist, maybe had no interest in social convention, then it, hopefully, opens the door for other women to be that as well.

Rebecca: Another thing I find really interesting about this essay is that it shows how real women who actually lived can still get turned into cliches. I think that there is a way in which we have a hard time, like "we" as in the culture, have a hard time thinking about women as fully fledged people, but also historical figures as fully fledged people, so, how about we talk about a little bit about how women get cast as tropes, especially in historical writing, or even in historical writing.

Leila: Yeah, yeah, and I think this goes back to the issue of representation that I was talking about earlier. We're so used to conceptualizing nursing as a feminized field that Nightingale so easily fits into this category. In this case, the category was kind of built around the myths we tell about her, also, but whereas her work in mathematics and statistics has required more recovery work. We don't typically expect to find women in mathematics, so we tend not to look for them there. This idea that historical figures present themselves to historians in an objective way is just trash, and that if historical women just presented themselves in historical record by merely existing there, then the recovery work done by mainly women historians throughout the, starting mainly in the 70s, wouldn't have been necessary in the first place.

Anna: So, I was thinking about this idea of women being turned into cliches, and I think this is one of those really deep historical issues that isn't confined to sort of like a profession, which is a modern phenomenon like nursing. I think that this goes back to the sort of turning science or logic or various liberal arts sort of into these female figures. Go with me on this.

Rebecca: [crosstalk 00:13:59] and like really picturing the, yeah, liberal arts...

Anna: Right, so there's...

Leila: Yeah.

Anna: Yeah, you can look at the phrontist pieces of, especially early modern printed books really go in for this kind of thing, but the personification of various ideas or concepts as women is like a really tenacious thing. It sort of still happens, I think, but there's also like Columbia as the figure of America, Britannia as the sort of figurehead of Britain, and I think that part of, my theory, I guess, about part of the reason why women are so often turned into cliches like this is because that's just how women have been allowed to exist in public as figureheads for ideas or concepts or, in the case of Florence Nightingale, an entire profession. And maybe part of the reason for that is because if you just have one woman who represents nursing, not only does that sort of control the image of a profession or a field or a concept, it also sort of precludes any other representation because you have this idealized figure that's supposed to encompass all of science or all of the ideals of Britain in this lovely woman in drapey clothing, and there's no reason to involve women in other representations of those ideas because you've created this idealized figure that's supposed to stand for everything that is valuable about what you're trying to represent.

Anna: So, and that's my sort of crunchy visual culture theory about this kind of cliché-ifying of women, and especially in, I think, professions, as we get into sort of the modern period, Nightingale's period, the professionalization of both the sciences and medicine in other fields also meant the masculinization. So, there's a reifying of what it means to be a professional and to be engaged in this field at a professional level, and that kind of reifying force is always going to just sort of shave away women. So, I think what you said, Leila, about how we remember Florence Nightingale but not the hundreds of nurses that she trained is really important for kind of thinking about how these types of representations and this mode of representation is part of the reason we have such a hard time recovering the history of everyday women in science and medicine.

Leila: This question I have goes along with representation as well, and representation kind of how it specifically applies to women, and it's not specific to nursing, but it's this idea of trying to impose sexuality onto historical figures. And Joy addresses the long standing assumptions by historians that Nightingale was a lesbian because she didn't have a traditional marriage that would've been expected of her. Instead, she lived with women companions throughout her life. And historians have also guessed at astronomer Maria Mitchell's sexuality, who also never married and surrounded herself with the company of women. And Joy calls this queer instead of guessing at Nightingale's sexual orientation. So, what are your thoughts on why framing these women as queer instead of lesbian matters?

Rebecca: So, this is one of those issues that I am super fascinated by and never have a satisfying, like straightforward answer for, which is probably why it's so fascinating. On the one hand, there is something weird about the idea that calling Florence Nightingale a lesbian is sexualizing her, but tacitly assuming that she's straight is not sexualizing in any way. But, I also understand all of the cultural context that means that that's a thing. And I do feel, in general, that sometimes historians, they can be too quick to define people, but they can also be too quick to protest when historical figures are given modern LGBT labels. They can say, "Well, these are anachronistic, so you can't call them that, even if various kinds of evidence apply." And that can be a way of erasing LGBT people from the historical record in the name of accuracy.

Rebecca: On the other hand, I do really like the word queer, and I like how it's used in this context. I think it can be a valuable way of talking about Nightingale. I think it emphasizes that Nightingale structured her life in a way that was radical by not getting married by kind of centering her personal life and her professional life around women. It doesn't really matter who she was or maybe wasn't sleeping with, it really matters that she built her life outside the gendered expectations of her time, and that's what I think queer has come to represent in historical writing, which is pretty cool. As someone who has worked in the museum field and as public historian, I've also seen this come up in really interesting ways in historic houses by significant women. Especially, I feel like, it comes up in significant 19th century women.

Rebecca: In particular, the Jane Addams Hull-House in Chicago has done some really interesting work, often publicly grappling with the way to talk about Jane Addams' partners who were women and, I think, at least one of whom she lived with for decades. And the whole house has, their historical interpretation is, in general, been very socially conscious, and so, I feel like they had a place where they could enter that conversation. Also, interestingly enough, currently, the National Trust in the UK in explicitly trying to look at different ways to examine what they call LBGTQ history in historic houses across the UK.

Leila: Wow.

Rebecca: Yeah, yeah. It's because it's the 50th anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality in Britain, so I feel like the BBC has all this stuff going on and the National Trust has this stuff going on. They have, of course, gotten pushback from all of the lovely conservative newspapers in the UK, but they seem to be doing some cool stuff there. So, British people listening to this, go check that out.

Rebecca: I can't, I'm sad.

Leila: Yeah, I agree with so much of what you said, and I'm in no way an authority on LGBTQ history in science, this is just kind of the observations that I've made, that historians have made, about women in science.

Rebecca: And I did want to say that neither am I. Although, actual historians of this stuff should feel free to correct us on anything.

Leila: Yeah, yeah. Leave us a comment. But, the imposing, or at least guessing at sexual identities on historical figures who weren't out or clear about their sexuality in their personal writings, this seems to be unevenly distributed in that I find that it seems to happen to women historical figures more than men. And so, I think that goes with your concern, Rebecca, that calling Nightingale a lesbian could sexualize her. It feels like it can border on the male gaze rather than genuine historical recovery. And also, perhaps it is unevenly applied to women because the gender social rules were so, so strict for women that really all they had to do was fart in public to break them. So, when women stepped out of line, it really was so much more visible.

Anna: And I just want to add...

Leila: Yeah, yeah.

Anna: Just one thing about that, what you say about women stepping out of line is much more visible, it's completely acceptable for men in Nightingale's period to have an entirely homo-social group that they build their lives around.

Leila: Yes.

Anna: It is not acceptable for women to do that.

Rebecca: Well, even more interestingly, my understanding is it's acceptable for young women to do that, but then you get married, and you give up all of your girlfriends. Because you're not [crosstalk 00:24:11]. Yeah.

Anna: You're not supposed to have any kind of professional life anyway, you're supposed to be married, and to engage in that kind of professional life and be surrounded mostly by women is just so far outside the norm.

Leila: Yeah. Yeah, and that it was acceptable for men at this time to kind of have a, as you said, homo-social group, is that our expectations of masculinity have changed since then as well, right?

Anna: Oh, yeah.

Leila: That having that kind of close intimate circle of male friends is kind of stepping outside of modern toxic masculinity, right? And so, I think there's that going on there as well. Our changing expectations, and not just what women can and cannot do, but also what men can and cannot do.

Rebecca: And it's also worth noting, kind of, this goes more to the problem of maybe why it feels like it is placed upon women, without explicit evidence that a woman was queer or lesbian or bisexual or whatever, more than men, I mean, besides sexism, but I think also the fact that there were visible gay male spaces in the 19th century and there were not visible gay female spaces also because of the fact that male homosexuality was criminalized. I think a lot of people who research gay men and the history of male homosexuality get a lot of their evidence from police records. And so, even then, you have to come at it sideways, but at least the police records exist, which is terrible, but also really great for historians.

Leila: Yes.

Rebecca: And there isn't an equivalent for women.

Leila: Yeah, that's true.

Rebecca: Only people being snarky about women, and people were snarky about all women who stepped out of line.

Leila: Yeah, absolutely.

Anna: Okay, so, speaking of tropes and representation, let's switch over to Jenna's article, Why Are We Still Talking About The Naughty Nurse? This is an interesting article because it takes a look at the broader cultural and social representation of women nurses, but in the process, Jenna also explores the feminization of the field of nursing, something that has happened in other scientific fields as well. So, please welcome Jenna Tonn, contributing editor for Lady Science.

J. Tonn: Hi. It's great to be here, thank you for inviting me.

Anna: Welcome.

Rebecca: Yay! Happy to have you.

J. Tonn: So, to introduce myself, my name is Jenna, I'm a historian of science. I got my PhD in 2015 from Harvard, and my research is mostly about women and gender in science in the 19th century, so I'm writing a book about the social lives of men and women and experimental biological laboratories in the 1890s to the 1930s. And, currently, I'm a visiting assistant professor in Boston College in history and science and technology studies.

Rebecca: Welcome. So, just to kick us off, what drew you to write this particular essay?

J. Tonn: Yeah, so the idea for this essay actually came from a conversation I was having with my students. Every year, I teach a seminar called Women in American Medicine, and there's a unit where we read about the history of nursing. And my students were shocked how little they knew about the history of nursing and how complicated and interesting and fascinating the topic has to be. And one of the questions one of my students asked is, if the history of nursing is such a serious and complicated topic, why does everyone dress up as sexy nurses on Halloween? Like, what is the deal with this tension between a really serious sort of set of historical questions and the pop culture world where women are overtly sexualized and where you can log onto Amazon and see 10 thousand or more, there are probably more, skimpy nurse costumes that you can buy for a night out in October? So, that was like what was really getting me thinking about trying to connect large conversations in pop culture about the sexualization of women's bodies with these more detailed, and I think really thoughtful, conversations in the history of medicine.

Anna: And this is exactly the kind of thing that we really love to do at Lady Science to just sort of interrogate something that seems like a very normal part of the texture of our modern world and figure out where it came from. So, why are we still talking about naughty nurses?

J. Tonn: Right, that is the question. I mean, I think people have different answers, but one of the things that I found myself concluding as I was doing the research for this article is that thinking about nurses in the context of pop culture actively erases the hard work that mostly women do as nurses. It, in some ways, takes the caregiving role, it sets it off side, it sets it in a more demeaning place, and it allows us not to have to think really hard about the fact that caregiving is really central to our experiences at home and in the hospital, and it also allows us not to think really hard about the fact that we all are sick at various times in our lives and want to get better. And we all have physical interactions with nurses in hospital settings or in doctor settings that are often difficult and uncomfortable because we are not feeling great.

J. Tonn: And so, I think the sexualization of nurses is overlaid onto this larger uneasiness with this caregiving role and its association with women and women's bodies and the feminization of certain kinds of labor practices. So, that was one of the things that I think I found myself getting to towards the end of this article.

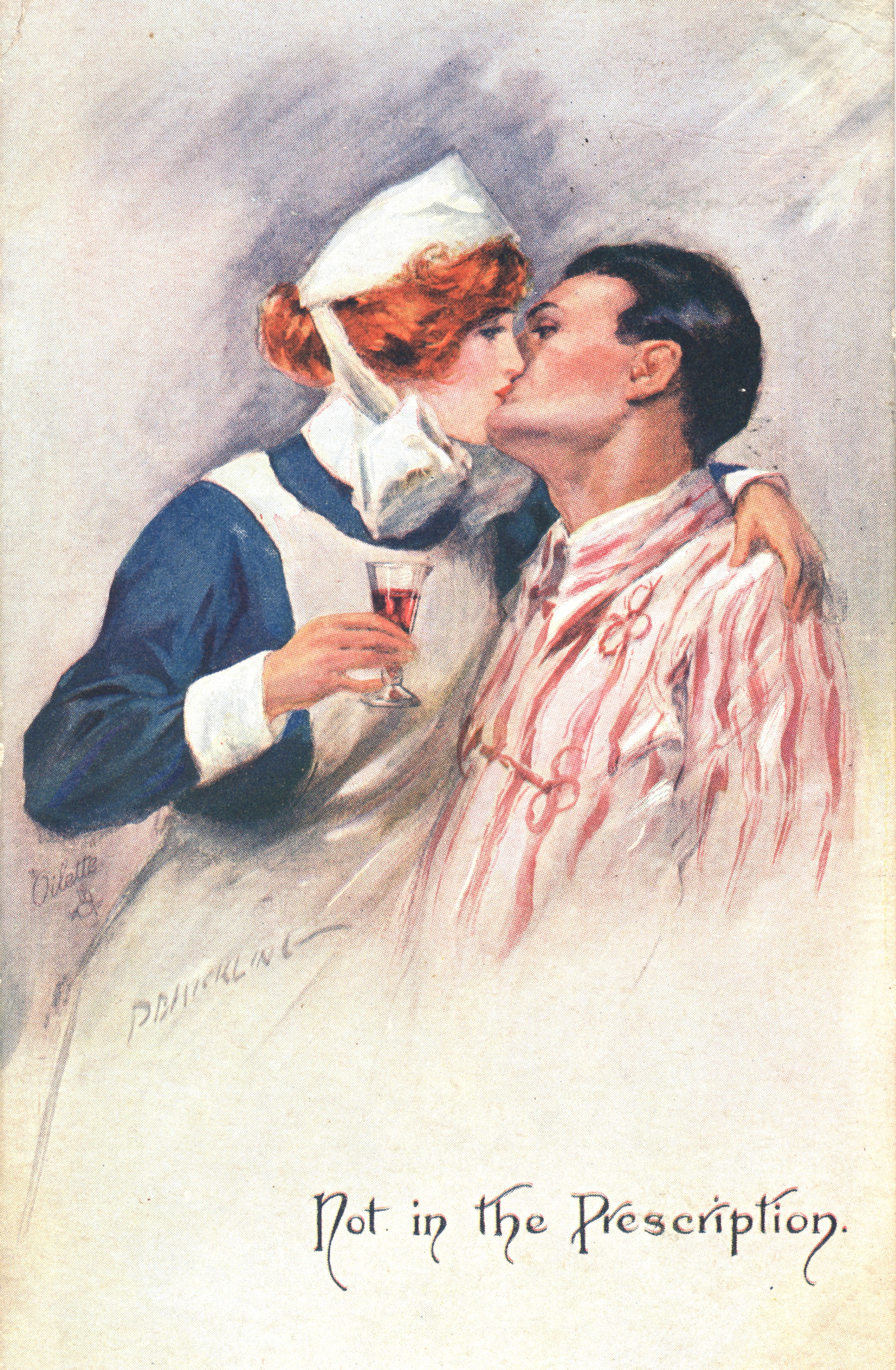

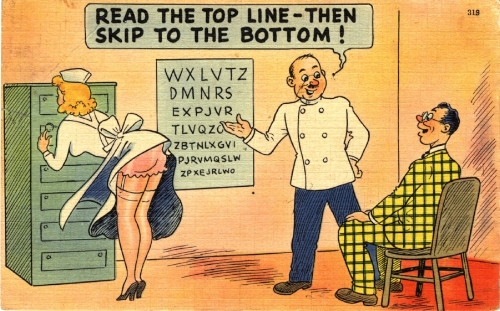

Leila: Yeah. Some of the tropey images and stuff that you pick up on that nurses have kind of been plugged into, you included some really great illustrations to go along with that, and I really enjoyed being able to go through them when we were laying out the issue. But, each one of those kind of falls into that, those tropes that you're talking about. There's the one of the angelic representation of a nurse with her arms outstretched in front of a red cross, one that looks like an intimate moment with a nurse and her male patient, and then a couple of others that were really fun, well, you know, kind of fun. Fun in kind of a...

J. Tonn: Fun in a particular way, yeah.

Leila: Yeah, yeah. In a kind of like, "Hm, that's a interesting historical thing." But, what was your favorite that you found while you were doing your research?

J. Tonn: Yeah, so, a lot of these I found from the National Library of Medicine's Zwerdling Postcard Collection, and you can google it and they have like hundreds and hundreds of these, and I think what I really liked, besides being disturbed by a lot of them, was the shift that you see if you put some of them in historical sequence. So, the one that you were talking about, there's one from around World War I, and what we see is we see a white nurse in a very stereotypical nurse outfit kissing a white patient who's come back from the front, and the tagline is not in the prescription, because she's holding a little bit of medicine. And so here it's sort of the chaste, virginal kiss, it's very much in the context of romantic representations of women. You also get the sense of, since men have gone off to war, they then deserve not only to be taken care of, but to be taken care of by sexually available nurses. There's a lot going on in this postcard.

J. Tonn: And then, just a few decades later, around or after the time period of World War II, you have a completely different visual representation of nurses. Like, the nurse is a pinup girl, the postcard that I'm talking about, what you see is you see a very scantily clad woman nurse bending over, so you see her rear end, and there are two clothed men, one doctor, who says, "Read the top line and then skip to the bottom." Who's talking to another male patient who's doing an eye exam. So, hopefully you can post the image so people can see it. And, I think what is fascinating about this is the casual sexism that's inherent in the representation of the nurse and the presumption of the male gaze. So, here we have two basically clothed men looking at a very scantily clad woman, and I think that, the shift from the more chaste kiss to the overt sexualization of women's rear ends.

J. Tonn: Historians talk about this moment as a crisis of masculinity that surrounds soldiers' return from the home front in World War II. So, you suddenly have anxieties around new kinds of injuries that soldiers have, you have rising status of nurses and hospitals that are expanding that actually need nurses who are technically trained to do anesthesia work, to do rehabilitation, to work in these new, one might say, expansive hospital industries. So, as the status of nurses are rising, what do you do to try to reverse that? You create a hierarchy and you use overt forms of sexual objectification to, essentially, undermine the professional expertise that these women have to have to do the jobs that they're doing.

Rebecca: Can I just jump in and say, this just hit me as you were describing it, but the eye exam image, it's literally the male gaze.

J. Tonn: Yes. Oh, yeah.

Leila: He's literally testing his male gaze.

J. Tonn: Right, right. I love that reading of it. I mean, that's the thing that makes it so interesting, it's like so overt, it's too overt in a way.

Leila: Right.

Anna: So, you write a little bit about how race and class intersect in American nursing, but how these complicated dynamics are completely absent from our sort of popular culture idea of what nursing entails and the tropes of nursing. You write that, quote, "Gender expectations allowed women to seek meaningful employment as nurses, they also revealed how relationships between women fragmented along racial and class lines." Can you talk a little bit more about what this fragmentation looked like?

J. Tonn: Sure. Yeah, and I think this is one of the really important aspects of thinking about the history of nursing, and also a really important aspect of thinking about feminism more broadly and women in science more broadly, that it's impossible to talk about all women as part of the same group. And when you start thinking about women as an essential or universal population, what actually happens is you start to see that gender solidarity does not always cross class lines or lines of ethnicity or lines of race or lines of religion, and you see that quite a bit in the history of nursing. So, when you read about the earlier 19th century history of nursing, just the point in time when nursing becomes a professional occupation for women, which is really great for women and also really challenging.

J. Tonn: So, it's really great because it offers them a chance to get paid to do work outside of the home that is appropriate to their gender performance in the world, but it's also really hard because this work is underpaid, super physically demanding, and, often, the oversight is such that women are trapped in a hospital, essentially, so that they're able to do their duties in a timely way. And what you learn about in this context is that you often have sort of vertical forms of harassment among women, so you have head nurses who are quite controlling and abusive towards nurse trainees.

J. Tonn: And the other thing that you see is you often see nurses themselves who form specific cliques based on their origins or based on their class or religion. And when you talk about nursing more in the 20th century, what you often see, especially in the context of the history of African American nurses, is white women who are forming major nursing organizations who are excluding black women for racial reasons. And you also see, I would say more broadly, one of the things that historians of African American nurses talk about is that to think about black women as nurses, you actually have to think about the long history of nursing and slavery. So, in the context of slavery, enslaved women did not have a choice about whether or not they had to assume caregiving roles.

J. Tonn: So, Sharla Fett has this great book called Working Cures, and she talks about how in the context of slave plantations, older enslaved women were forced not only to care for communities of slaves on plantations, they were also forced to care for the white slaveholders' families. And so, to talk about the history of race and nursing in this context means casting your gaze back into the 19th century and then looking forward into the 20th century. So, talking about nursing gets us into all of these other larger questions about women and the very different ways in which they've navigated the world.

Rebecca: That's a great place to end, I feel like.

J. Tonn: Okay. Great.

Rebecca: So, yeah, thanks. Sorry.

J. Tonn: Thanks for having me.

Rebecca: Yeah, thanks so much for chatting with us. Like Leila said, we'll include both the article we discussed in the episode notes, and links to some of those nursing illustrations that we talked about.

Anna: At the end of every podcast, hosts and guests will unburden themselves with one thing in the news, their work, or in the world in general that is just annoying the crap out of them. This is one annoying thing.

Leila: So, one thing that's been annoying me for some time, and calling this an annoyance is an understatement, but I'm getting increasingly uncomfortable with the rhetoric of economics and capitalism making its way into social justice activism. Quote, "It's bad for business" has become a popular argument for opening our borders to immigrants and refugees, and for allowing trans folks to use the restroom that aligns with their gender identity. And in the past few months, Texas, where I am currently living, has been embroiled in issues of immigration and trans rights over the past year. So, these economic arguments are being wielded quite a bit by progressive politicians and advocates against discriminatory immigration and LGBT legislation.

Leila: For decades, immigrants of all stripes have been scapegoated as a drain on the economy, all the while stealing scarce jobs from hardworking, homegrown Americans. And we know this isn't true, as study after study, economist after economist has told us. So, you've seen the rhetoric of economics to avoid legislation that protects immigrants is a compelling one that is grounded in well-documented research. A similar stance emerged in favor of trans rights when North Carolina passed their infamous bathroom bill last year, and this has served as a precedent for what Texas has been working toward also. In the wake of North Carolina's legislation that barred trans people from using the bathroom that matched their gender identity, businesses suffered when high profile bands like Mumford and Sons pulled North Carolina from their tour. And, in an increasingly socially liberal, national, and global society, regressive discriminatory legislation is becoming unprofitable, which is good in its own way, and reaching for economic arguments is low hanging fruit in a capitalist hungry society.

Leila: So, I understand why it's an attractive argument, and it does seem to be somewhat effective. The problem I have with this, however, is that, instead of advocating for immigrants and trans folks as holding inherent value as humans, they are being reduced to dollar signs. Their civil rights are being quantified on a spreadsheet. And quote, "It's bad for business" is not a social justice sentiment, it's a sentiment rooted in the best interest of a capitalist institution. It de-centers the humanity and civil rights of the marginalized communities that are effected. And I don't really have much hope that politicians will abandon economic-based arguments for social justice, but those of us who are interested in civil rights absolutely should.

Anna: Okay, so, my one annoying thing this week is a man congratulating himself publicly of being attracted to his wife. So, if you're on Twitter, you probably saw this, and I have just been fuming about it since I first came across this. There is a person described as an American entrepreneur, I don't know if that means he sells Herbalife on Facebook or what, but Robbie Tripp, who posted on his Instagram a picture of him and his wife at the beach in their beach clothes, and he posted this long caption about, I'll quote a little bit of it but not all because it's gross. Quote, "I love this woman and her curvy body. As a teenager, I was often teased by my friends for attraction to girls on the thicker side."

Anna: So, first of all, this woman is your wife, and you don't get a cookie for being attracted to your wife, no matter what her body looks like, that's just sort of basic human decency. But the thing that got really irritating about this is that it got picked up, the first one that I saw was Buzzfeed picked this up and wrote a little non-story about this, and their subheading was, the heading was something like, Man Is Getting Praised For His Support Of His Curvy Wife, or whatever, and then the subhead was, I'm not crying, you're crying.

Anna: And it's just, I think that it's really, first of all, it's really dumb that we're paying attention to this dude at all. Like, this is not newsworthy. But, the way that it has been made newsworthy by places like Buzzfeed, is trading on this idea that in order for body positivity, which has been historically a movement led by women, that somehow we need men to validate the idea of body positivity, first of all, and to do that by making their sexual preferences public about what kinds of women they're sexually attracted to. And then, another thing that he does is he admonishes other men for having their own sexual preferences about women's bodies. So, that's just what every girls wants to be embroiled in is a conversation between men about whether or not they're worthy of love based on the size of their butts. That's really fantastic.

Anna: And, I guess, the final thing that just really irritates me about this is that women who are, even if they're not explicitly in the business of being body positivity advocates, women who fall outside of sort of straight model sizes posting pictures of themselves or saying things about themselves that this guy has said about his wife, are always, always, always met with concerned trolling about the dangers of being overweight, or just outright harassment of people telling them that they're disgusting whales or whatever. So, there's a real double standard about who gets to be invested in body positivity and who we get to listen to about it, and I don't know. Like I said, it's a non-story, but I find it really irritating and I just, you don't get a cookie for thinking that your wife is attractive. I don't understand. I'll let it go there, otherwise I'll just go on a, I'll spiral out of control.

Rebecca: So, I feel like it's very on brand that we are all annoyed about either the patriarchy or capitalism. I'm going to return to-

Leila: Or both.

Rebecca: Or both. I mean, we're usually annoyed with both, and I feel like this is probably going to be a recurring theme. For my one annoying thing, I'm going to return to capitalism. So, this is something that has been annoying me for a while, and I think one of the things that annoys me is that whenever I think this particular story is over, it rises like a zombie and I want it to go away again, and it doesn't and I get mad. I'm really tired of technology companies who want to reinvent public transportation infrastructure, which sounds really fancy pancy when I put it that way, but it's just driving me crazy.

Rebecca: About a year ago, I was talking to a friend who lives in Oakland, California, which is relevant because said friend knows people who work at Google. And so, there's a guy that she knows who works at Google, and the Google guy was talking about the new plan to attach self-driving cars together in a caravan, and then those caravans would travel along specific routes built only for them, and use them to transport goods a long distance. And, in response, I was like, "You have literally just described a train." And this was dismissed. Then, at Christmas, I guess then this idea became more of a thing, and by Christmas there had been news about it that my family was talking about some article with the related idea. And so, I was still like, "You've just described a train."

Rebecca: So then, back in June, this escalates to Lyft launched their shuttle service, which lets users, and I quote, "Ride for a low fixed fare along convenient routes with no surprise stops." Which sounds lovely until you think about it for two seconds and realize they're talking about a bus. They literally just described a bus, and buses exist in their thing and we don't need privat buses, necessarily. And, yeah, it's easy to make fun of because we're all familiar with buses, but there are these dangerous, I think genuinely important, social implications to think about because whether it is, I mean, trains are semi-privatized, but there's a public/private aspect to them. Buses are usually a public good in some way, it's called public transportation for a reason, and you're taking all of those things and you're just completely privatizing it. You're saying these things are imperfect, and sometimes really crappy, so we're just going to have a private company totally fix this problem. But, if something is completely privatized, it's no longer available to the same people. That has, of course, racial implications, it has gender implications, it has class implications.

Rebecca: And I just kind of want all of that to go away. I don't want us to think that Lyft is going, or Google or self-driving cars, are going to solve all of the public transportation issues in the country. Until it does, I will probably keep being mad about it. Yeah. Grr. Stop ruining public goods.

Anna: I think that's a great place to sign off today. So, if you have questions about any of our segments, tweet us at @ladyxscience or #LadySciPod. To sign up for our monthly newsletter, read monthly issues, pitch us an idea for an article and more, visit ladyscience.com. We are an independent magazine and we depend on the support from our readers and listeners. You can support us through a monthly donation with Patreon or through a one-time donation. Just visit ladyscience.com/donate. And, until next time, you can find us on social media at Facebook and Twitter.